I love werewolves so much, you guys. I can’t even convey it to you. Really, I can’t. I’ve fallen into a feverish mood of just how much I love werewolves working on this post and how badly it rends my soul that they are portrayed so poorly across almost all media – and how the legends of them are all but forgotten and the ones everyone remembers are massively misinterpreted.

This really is my calling in life.

So let’s go. This is the longest werewolf fact to date, because this is a big deal to me and I want to get all these facts straight, so try not to get intimidated!

The Howling, the #1 movie that helped a generation think werewolves are similar to the legend of Peter Stubbe

I was preparing a poll for my patrons to decide the topic of the next werewolf fact, since my patrons have now decided that werewolf facts from here on (at least until the upcoming werewolf fact book, Werewolf Facts: A Guidebook to Folklore vs Pop Culture, is compiled and published!) will be deep-dives into specific werewolf legends.

However, while preparing this poll, I figured… why not google the most famous werewolf legends, to see what people would know the best and thus recognize and be interested in hearing more about?

As someone with two options in the poll already – those options being “Bisclavret” and “Peter Stubbe (and how his tale is not a werewolf legend)” – I was… very frustrated by the search results.

I ended up not running a poll this time, because it’s so important to me to knock out these lies about what is and isn’t a werewolf legend, like the nonexistent “wulver” and how the Beast of Gevaudan isn’t actually a werewolf legend, either.

Now, it’s important for me to note that I’ve already touched upon this once in a previous werewolf fact, because I personally find this to be a very big deal in terms of something werewolf studies has so horribly, tragically wrong, and people very seriously need to stop circulating this false concept and amateur misreading of a legend for which we have a very exact historical record. I have also referred to this in greater detail in my book, The Werewolf: Past and Future, because – again – it’s such a massive issue to me that this is considered such a “famous” werewolf legend.

However, I am going to detail it still further, because it’s so important to me that people realize just how much Peter Stubbe was never referred to as “The Werewolf of Bedburg” and was, in fact, never even referred to as a “werewolf” at all, not in the original accounts.

Now, in werewolf legends, not all “werewolves” are referred to as “werewolves.” This is something I’ve covered several times before. This is largely because, when you look at folklore and mythology, you don’t get clear guidelines as to which creature is what.

That being said, Peter Stubbe’s account comes from a time period when people were, in fact, actually using the term “werewolf” and categorized things in a fashion more in the spirit of today, as opposed to so many of the older legends we now refer to as “werewolf legends” because they formed the basis of so many werewolf concepts that we still use.

Peter Stubbe’s account occurred at a time when the Catholic Church was indeed using the terms “werewolf” and “sorcerer” and they referred to very different, very specific things. This is something that separates something like the later-period werewolf trials from much earlier legends that never made use of the word “werewolf,” like various Greek werewolf legends, etc. For more info on that, see my post on What Is a Werewolf?.

For now, let’s get back to all the reasons why Peter Stubbe’s legend – like the also sadly famous Beast of Gevaudan – is not a werewolf legend at all.

First, let’s talk about the account itself. In fact, let’s go over it in some detail. I am getting all quotes from The Werewolf in Lore and Legend by Montague Summers, pages 253-259 in the 2012 Martino Publishing edition (one of the slightly better editions).

Montague Summers opens by claiming Stubbe’s account to be “one of the most famous of all German werewolf trials” (253), despite it not being a werewolf trial at all but in fact the trial of a sorcerer. As Summers himself says, Stubbe goes by many names: “Peter Stump (or Stumpf, Stube, Stubbe, Stub, as the name is indifferently spelled–and there are other variants)” (253). In my case, I’m going to use Stubbe.

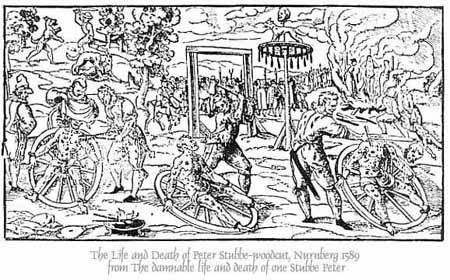

Peter Stubbe was executed in Bedburg, near Cologne, on the 31 of March in 1590. At the time, this was a big deal – or, in Summers’ words, it “caused an immense sensation” (253) – and has been referenced since in popular works. A pamphlet detailing the events of Stubbe’s actions and his execution after his capture is published in Summers’ work, and he says he has “reproduce[d] it in full” (253). This seems to be true, as he didn’t feel the need to insert any references to werewolfery into the account.

The pamphlet begins thus, on page 253 of Summers’ work:

A true Discourse.

Declaring the damnable life

and death of one Stubbe Peeter, a most

wicked Sorcerer, who in the likenes of a

Woolfe, committed many murders, continuing this

diuelish [devilish] practise 25. yeeres [years], killing and de-

uouring [devouring] Men, Woomen, and

Children.

Who for the same fact was ta-

ken and executed on the 31. of October

last past in the Towne of Bedbur

neer the Cittie of Collin

in Germany.

Notice he is referred to here as a “Sorcerer.” And again, on the following page, the discourse opens with “Stubbe, Peeter, being a most / wicked Sorcerer” (254).

Sorcerer and sorcery – where do they call him a “werewolf?” They never refer to Stubbe as a werewolf once, nor do they accuse him of “werewolfery,” a term seeing relatively frequent use in this time period.

The fact that Stubbe supposedly turned into a wolf has retroactively made scholars refer to him as a “werewolf,” but he was never even called that. Throughout the account, we only ever see him referred to as a sorcerer. For instance, “the great matters which the accursed practise of Sorcery” (254). He is, in one instance, referred to as a “hellhound” (254), but not as a werewolf. The writer describes Stubbe as having been a man possessed by a “Damnable desire of magick … and sorcery” (254) for his entire life, starting especially since he was twelve years old. He made a deal with the Devil later in life…

The Deuill [Devil/Satan] who hath a readye eare to listen to the lewde motions of cursed men, promised to give vnto him whatsoeuer his hart desired during his mortall life : wherupon this vilde wrtech neither desired riches nor promotion, nor was his fancy satisfied with any externall or outward pleasure, but hauing a tirannous hart, and a most cruell blody minde, he only requested that at his plesure he might woork his mallice on men, Women, and children, in the shape of some beast, wherby he might liue without dread or danger of life, and vnknowen to be the executor of any bloody enterprise, which he meant to commit (254)

So as you can see, Stubbe was a messed up guy. And he only asked for the shape of “some beast.” That doesn’t sound like “werewolf,” does it? Continuing…

[The Devil] gaue until him a girdle which being put about him, he was straight transfourmed into the likenes of a greedy deuouring Woolf, strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkeled like vnto brandes of fire, a mouth great and wide, with most sharpe and cruell teeth, A huge body, and mightye pawes : And no sooner should he put off the same girdle, but presently he should appeere in his former shape, according to the proportion of a man, as if he had neuer beene changed (255)

Well, Stubbe liked that a lot, because he was a sicko and wanted to go do sick things. It didn’t matter what animal it was – but the Devil chose to let him turn into a wolf.

Now, a few elements of his story are similar to a few other werewolf trials – like Jean Grenier – of around the same time period, and we also have some older stories of things like skins and salves being used to turn someone into a wolf. So why do I separate this?

Because in this time period, werewolves and sorcerers were both believed in, and Stubbe was not referred to as a werewolf. His legend does not have crucial elements in common with even other werewolf legends of the time period, like a lack of self-control/insanity. Stubbe was fully aware of his actions and willfully doing these things and taking this form. His animal form could have just as easily been some kind of cat, unknown beast, or bear, or whatever, because he’s not a werewolf – he’s a sorcerer.

So Stubbe went around committing his atrocities “in the shape of a Woolfe” (255). He even would walk up and down the streets and “if he could spye either Maide, Wife, or childe, that his eyes liked or his hart lusted after, he would … in the feeles rauishe [ravish] them, and after in his Wooluishe [wolfish] likenes cruelly murder them” (255). Sound familiar? Yeah, that’s The Howling. It’s sad that this has infiltrated many levels of popular culture now. Werewolves were, before Stubbe became retroactively deemed a werewolf, never associated with sexual crimes.

It’s pointed out at this section of the account while detailing how disgusting and lecherous and murderous Stubbe was, going around eating people and babies and lambs and other animals, that he would eat them raw and bloody “as if he had beene a naturall Woolfe indeed, so that all men mistrusted nothing lesse than this his diuelish Sorcerie” (255). Again – sorcery. Not “lycanthropy” or “werewolfery” or “werewolf” or anything like that. And I’m not gonna lie, this guy’s legend is very messed up. It disturbs me to have anything like this associated with werewolves. It was never meant to be, and I am upset that scholars have decided it should be.

The account goes on to detail how Stubbe violated several women, including his own sister, and even begot children as a result. I won’t go into too many details about that, but it’s just more points toward this not being a werewolf legend, as it stands out starkly as the only “werewolf legend” that ever involved anything of the sort. But we once again get the reference to “likenes of a Woolfe” (256) – several more, in fact. We also get a “transformed man” (257), which again is not “werewolf,” as well as referring to him as “this light footed Woolfe” (257) and “this greedy & cruel Woolfe” (257).

Eventually, people did catch Stubbe, but only because they caught him returning to human shape after removing his demonic girdle that gave him a wolf form as long as he wore it. He was then taken and confessed to all his crimes, saying that “by Sorcery he procured of the Deuill a Girdle, which beeing put on, he forthwith became a Woolfe” (258).

Then they sure did mess him up. His execution was that he would “first to haue his body laide on a wheele, and with red hotte burning pincers in ten seueral places to haue the flesh puld off from the bones, after that, his legges and Armes to be broken with a wooddenn Axe or Hatchet, afterward to haue his head strook from his body, then to haue his carkasse burnde to Ashes” (259).

The account concludes…

Thus Gentle Reader haue I set down the true discourse of this wicked man Stub Peeter, which I desire to be a warning to all Sorcerers and Witches, which vnlawfully followe their owne diuelish imagination to the vtter ruine and destruction of their soules eternally, from which wicked and damnable practice, I beseech God keepe all good men, and from the crueltye of their wicked hartes. Amen. (259)

Sorcerers and witches. Not werewolves.

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of mentioning that this trial took place at a time period when other werewolf trials also occurred. Other werewolf trials around the same period referred to their accused as “werewolves.” However, Stubbe was – as mentioned – never once referred to as a werewolf. Careful care was taken to avoid this. He is “wolf-shaped” and “sorcerer.” Always “sorcerer,” never “werewolf.”

Around this same time period, there exist assorted examples of accusations of “werewolfery” and of “being a werewolf.” One such example is the parliament of Franche-Comte issuing a decree in December of 1573 (years before Stubbe’s trial), as detailed on page 146 of Matthew Beresford’s The White Devil,

those who are abiding or dwelling in said places … to assemble with pikes, halberds, arquebuses, and sticks, to chase and pursue the said were-wolf in every place where they may find or seize him

Again, however, Stubbe was never specified as practicing “werewolfery” or “being a werewolf,” but he was on multiple accounts accused of “taking a wolf shape,” “sorcery,” and being a “sorcerer.”

This is because there was a huge difference between the two. Maybe I’ll do a separate werewolf fact on it, but it’s already touched upon across multiple facts of mine, like this one and this one along with others I linked earlier in this post.

Now we reach the point of asking: so why does everyone call Peter Stubbe a “werewolf”? Is it just because he turned into a wolf, which is in itself very sad, because everyone is ignoring the details? That’s certainly part of it.

One of the – possibly the – earliest source to refer to Stubbe as a werewolf is Richard Verstegan in his Restitution of Decayed Intelligence in 1605, on pages 236-237.

Please note these are directly copied from a not super great transcription. The original can be found here. For the sake of clarity, I have not altered the language in any way from the digitized edition, but I will break it down some.

In his definition of “werewolf,” he says,

Were – wulf . This name remayneth Aill knowne in the Teutonic , and is as much to ſay , as mans wolfe ; the Greeke expreſſing the very like , in Lycanthropos .

Ortelius not knowing what Wwere ſignifiech , becaufe in the Netherlands , it is now cleame out of rfe , except thus compoſed with WWolfe , doch miſ – interpret it ac cording to his fancy .

So, in the beginning here, Verstegan says that werewolves are “man-wolves” and refers to the Greek term “lycanthropos.” That’s all well and good. Then he goes out of his way to say that most people “misinterpret” werewolves “according to [their] fancy.” That’s ironic, considering he misinterprets werewolves in his next paragraph…

[werewolves] are certayne Sorcerers , who ha uing annoynted their bodies , with an Oyntment which they make by the inſtinct of the Diuell : And putting on a cercayne Inchaunced Girdle , doe not onely voto the view of others , ſceine as Wolues , but to their owne thin king haue boch che Shape and Nature of Wolues , ſo long as they weare the fayd Girdle . And they doc diſpoſe them felues as very wolues , in wourrying and killing , and moft of Humane Cicatures .

Of ſuch , ſundry haue beene takon , and executed in ſun dry parts of Germany , and the Netherlands . One Peter Stump , for beeing a were , Wolfe , and hauing killed thirteene Children , two VVomen , and one Mao ; was as Beibur , not farre from Cullen , in the yeare 1589 put vnco a very cerrible Death . The Ach of diucrs partes of his bom dy was pulled out with hot iron tongs , his armes , thighes , and legges broken on a Wheele , and his body laſtly burnt . Hee dyed with very great remorſe , deſiring that his body might not be ſpared from any Torment , fo his Coule might be ſaued .

He runs werewolves and sorcerers together. This wholly muddies the hard and fast definition of werewolves that was set during this time period. Sorcerers and werewolves are two very different things. What he describes here, and what Stubbe is, is a sorcerer, not a werewolf. And he takes it upon himself to say that Stubbe is a werewolf and that werewolves are sorcerers. Thanks for screwing entire generations of scholarship, buddy; not that Montague Summers exactly tried to help fix it. All things being equal, though, I can say with confidence that this Verstegan fellow was a very broad scholar and didn’t seem too interested in diving deep into the differences between werewolves and sorcerers or anything about werewolves in particular. Why he even bothered making these assertions about Stubbe being a werewolf is a bit of a curiosity.

To give you an even better idea of just how muddied the entire perception of Stubbe the sorcerer is, we see people today call him the “Werewolf of Bedburg,” but another scholar – Adam Douglas on page 162 of his book The Beast Within: A History of the Werewolf – calls him “the werewolf of Cologne” (Bedburg being very near Cologne; but which is he, the werewolf of Bedburg or the werewolf of Cologne? It’s almost like no one ever called him either one), and yet he himself also acknowledges indirectly through the use of quotes that Stubbe himself was – again – never once referred to as a “werewolf” during his own time period. He was always called a “sorcerer” and took a “wolf shape.” Never was he a “werewolf.”

Matthew Beresford is also guilty of spreading the concept of Stubbe as a werewolf in his own book, The White Devil, where he – on pages 146 and 147 – says Stubbe was “convicted of being a werewolf.” He was never convicted of being a werewolf. He was convicted of being a sorcerer. And again, of course, Beresford’s quotations from all primary sources make no mention of “werewolf.”

Even Montague Summers himself, who published the direct account of Stubbe in his book The Werewolf in Lore and Legend or just The Werewolf, claims that “[o]ne of the most famous of all German werewolf trials was that of Peter [Stubbe]” (Summers 253). But even looking at this account, and even elsewhere in his very own book laying out plainly the differences between werewolves and sorcerers and stressing the importance therein, Summers refers to Stubbe as a “werewolf.”

Granted, Summers is not necessarily known for his consistency, or even always his accuracy; regardless, his work to preserve the original accounts of legends is beyond commendable, and without him we may not still have the direct account of Stubbe’s trial with which to fully understand that Stubbe was never once referred to in his own time period as anything to do with a “werewolf.” We also wouldn’t have a lot of other things. I’ve used Summers’ work throughout my life, but his writing is still to be approached with a critical mindset instead of viewed as flawless.

Long – very long – story short…

tl;dr: Peter Stubbe was never, not even once, referred to as a “werewolf” or any other words associated with them in his own time period. The full and detailed account of his actions published the year of his execution never makes mention of anything to do with werewolves or the oft-used “werewolfery” during the time period. He is always referred to as a “sorcerer” and reference is made to his “likeness of a wolf,” but he’s never called a “werewolf.”

A werewolf and a sorcerer are not the same thing. It’s by no means 1:1. Saying that they are the same thing damages the study of werewolf legends and even the portrayals of werewolves in popular culture to an almost irreparable degree. It’s a misconception and a misreading of legend, folklore, and even historic accounts of periods during which such things were truly believed to exist. These misconceptions were popularized by academia and academia’s obsession with “new arguments” and the like. It isn’t a “new argument” to say Stubbe was a werewolf. It’s simply incorrect.

It is so important to note that there was an important distinction during this very time period between “werewolf” and “sorcerer.” This isn’t some kind of academic nitpickery about “well technically no one was a ‘werewolf’ in ancient Greece because the word didn’t exist yet!” or “’dragon’ really just means ‘serpent’“ or whatever. This is a simple, straightforward situation in which in the time period in question there was, in fact, a difference, and that difference is important to note hereafter because otherwise we should just throw all study of specific legends and myths and details of the time period and language and everything right out the window.

Peter Stubbe’s legendary account is one of a sorcerer, not a werewolf. It is not a werewolf legend. It’s a legend about sorcery and demonic magic.

Are there other instances in which we can blur the lines between between werewolf and sorcerer, potentially? Yes, perhaps. And someday I’ll get into those, in a different post. There are potential similarities between Stubbe’s account and some other werewolf accounts, but it’s endlessly important to note whether or not the word “werewolf” or “werewolfery” was used in accounts of this time period, since the word was in fact in use by this point in history.

And in Stubbe’s, those words were never used.

I cannot stress enough the importance of not entangling the account of Stubbe’s sorcery with werewolf legends. To draw one of my previous werewolf facts with a few additions – Peter Stubbe, by and large, just got mixed up in the obsession with “werewolf trials” (court trials), like the trial of Jean Grenier, who was accused of various crimes like cannibalism and “werewolfery” and “sorcery” (notice they are two different things). Grenier, however, was taken pity upon and deemed not responsible for his actions, and was sent to live the rest of his years in a monastery, where he lived peacefully for a time (but remained insane, as werewolves were associated with insanity during the late medieval and early modern period following the rise of scientific rationalism).

Whatever the case, for better or for worse, Peter Stubbe the sorcerer mistakenly remains the most immediate source for our modern horror movie werewolves that rather simplistically go romping about in search of flesh (in every sense of the word) to sate their hunger (also in every sense of the word).

And that’s a shame, because his legend isn’t a werewolf legend by any stretch. He could’ve turned into any animal, but just because his sorcerer animal form was a wolf, scholars have retroactively decided he was a “werewolf” instead of what he was called during his own time: a sorcerer.

(If you like my werewolf blog, be sure to check out my other stuff and please consider supporting me on Patreon! Every little bit helps so much.

Patreon — Wulfgard — Werewolf Fact Masterlist — Twitter — Vampire Fact Masterlist — Tumblr )