The final set of my Daily Werewolf Thoughts series! Again, these are not with the best formatting, and I wrote them for my social media accounts that are much less familiar with my work than most of my website visitors probably are.

Some very good ones in here, including big discussions of how berserkers are not “bear warriors,” Peter Stubbe not being a werewolf, and more, even including exactly why I personally love werewolves so much (and always will).

Enjoy, and I hope everyone has a wonderful Halloween!

Day 17- So how about this idea that werewolves are unholy? It’s a load of bunk, if you ask the old legends. That’s right, even in the Early Modern Period as werewolves became associated with satanic magic, the werewolf itself still wasn’t unholy – because the werewolf was a victim. And older than that, they simply weren’t at all.

Traditionally, werewolves were never considered unholy and, in fact, were often considered associated with God. We see this in the Werewolves of Ossory, among others, and if you believe Thiess or Thies of Kaltenbrun, the Werewolf of Livonia, there were also the Hounds of God who became werewolves and went into Hell to retrieve grain stolen by demons and battle Satan and his witches*. True, he was basically considered a crazy man, but it’s a fun concept to discuss. Likewise, werewolves in antiquity were never turned by Satan, as he does not possess such power. God, however, could turn people into werewolves for various reasons (I will discuss this further when I talk about the Werewolves of Ossory, one of my favorite tales). Those who became wolves by a satanic power were also still considered victims, such as Jean Grenier. As printed in records of his trial, preserved by Sabine Baring-Gould (shameless plug: https://www.amazon.com/Book-Werewolves-Superstition-Annotated-Translated-ebook/dp/B0CK4YY16Z )…

“The president went on to say that Lycanthropy and Kuanthropy were mere hallucinations, and that the change of shape existed only in the disorganized brain of the insane, consequently it was not a crime which could be punished. The tender age of the boy must be taken into consideration, and the utter neglect of his education and moral development. The court sentenced Grenier to perpetual imprisonment within the walls of a monastery at Bordeaux, where he might be instructed in his Christian and moral obligations; but any attempt to escape would be punished with death.”

Werewolves in legend were never driven off or harmed by holy artifacts, holy words, or holy ground – unlike vampires, demons, and other forms of undead, etc. Obviously, popular culture has had them now frequently associated with demonic imagery and acts, but I personally have never liked it, because I love werewolves and I think it’s pretty awesome that they actually -weren’t- associated with that kind of thing.

There’s a (an old, actually) Werewolf Fact on this and more, of course: https://maverickwerewolf.com/werewolf-facts/how-to-kill-a-werewolf/

*: It is extremely noteworthy that werewolves were NOT considered witches at any point in antiquity or the Early Modern period. They were different, and the difference remained important including and up to the famous werewolf and witch trials of the 1600s-1800s. I will discuss this some more in future thought posts, as it’s extremely important to my research and arguments and how modern scholars have spread so many outright inaccurate concepts as “fact” just to scrounge out more “arguments” for the “academic conversation.”

Image: the werewolf from Red Riding Hood (2011), shockingly one of my favorite werewolf movies, despite the werewolf doing the whole “werewolves are unholy” thing. Don’t let the teen romance fool you, it’s actually really good, and the werewolf is awesome!

Day 18- I am really sick of this concept of “millions of werewolves” like a zombie plague, no puns intended. You see it everywhere these days and have for over a decade, and it’s gotten very old. There’s a brand spanking new B-movie coming out later this year based on this concept, too.

Back in my day, werewolves came in 1’s. One werewolf, one story, very character-driven – made things dramatic and interesting and kept the werewolf horrific, not to mention unique. It also kept the werewolf as a relatable character, which is hugely important for such a story. Today, more often than not, werewolves come not only in “packs” (I will rant about this another time) but also in massive zombie hordes. In such a state, they aren’t even dangerous individually. One werewolf isn’t even a threat. They’re just a plague, like rats. In WoW, you have an objective in the worgen starting zone to “kill 80 worgen” in one go because there’s a blue million of them and they all absolutely suck (you have several objectives like this). It’s a terrible way to approach werewolves as a concept. At this point, especially with modern zombies being some infectious disease, why isn’t the story just about zombies? Why not just make it about some infectious rat-people plague, since that’s what it is?

If you see the scary monster in question slaughtered in droves, it lowers your perceived danger level of one as a threat. No matter what occasional thing has managed to arguably pull this off well regardless of seeing dozens on the screen at the same time (I have heard all the Aliens arguments*), it still ultimately works to make the single thing less intimidating. Especially when, in the case of werewolves, they’re largely only talked about as dangerous because they might infect someone… you know, like how modern zombies are handled.

Again, I have to say: if the werewolf is just a plague-carrier that comes in hordes, why not go with rats instead? Call them wererats if you must. It’d still be better than using werewolves.

I want to overall be positive in these posts, but often I cannot help myself. I hate the “werewolves as zombies”/”werewolves as rat monsters” trope, and after zombies already stole the “infection by bite” straight from werewolves. Today, it often takes an army of werewolves to do even one small thing. It’s just stupid and terrible. Use zombies for your zombie plague and leave werewolves alone.

image: worgen in Gilneas, the worgen starting zone (pre furry redesign)

*: I love Aliens, before you ask

Day 19- One of my all-time favorite werewolf stories is a Breton lai by the wonderful Marie de France. You guessed it: it’s Bisclavret, the Lai of the Werewolf. I adore this story.I relayed the entire story and discussed it in depth in this post here: https://maverickwerewolf.com/werewolf-fact-67-the-lai-of-the-werewolf-bisclavret/

But for the sake of brevity (although this will not be incredibly brief), I just want to say again that I adore this story because it’s such a classical tale of chivalry, knightly code, and a noble werewolf. I’ve always enjoyed that although the tale opens with a description of werewolves and what they are/how they are perceived, the werewolf in the story defies this description – and why? Because he’s a noble knight (and baron). Even when turned into a beast, he holds true to his chivalry and fealty. But frankly, such a concise description of werewolves is something I really enjoy too– “a werewolf is a man who suffers a change and runs wild in the darkest wood, horrible to behold, and devours men.”Solid gold. That’s a werewolf, right there.

Bisclavret is one of several similar tales of treacherous wives, a theme of more than a few medieval stories, who betray their good husbands. In this case, when she is told the truth of his being a werewolf, she is horrified and hides his clothing so he cannot return to human form. Guess there was a good reason he didn’t tell her the truth – but at least he found out she’s a terrible person, right? Treat your werewolf knight husband right. I mean, come on.

Similar to the tale of the Werewolves of Ossory, a moral of Bisclavret is not to judge a book by its cover, essentially. Bisclavret behaved noble and true even as a beast, and his king saw this and recognized it, sparing his life. The wife, however, was told the truth of her husband and was disgusted by the idea of him becoming a beast. In the Werewolves of Ossory, we see people who have been turned into wolves by God, and it becomes a test of others as well as the werewolves themselves – for others to recognize that even those beastly in appearance who behave in good nature should be treated in kind. More on this later when I discuss the werewolves of Ossory and the priest who met them.

If you’ve never read Bisclavret, it’s a wonderful story, whether you’re reading it for the werewolf or not. I highly recommend it. Someday in the future I’ll publish my own collection of old werewolf tales, with my own thoughts and translations etc. throughout… it’s on the backburner.

I’ve almost kept this up for the entire month! I’m so happy people actually read my ramblings. Thanks to you if you’ve stuck with them.

Day 20- One of the biggest tropes of modern werewolf media when they aren’t a rat plague, though sometimes these go hand in hand, is a “werewolf pack” and/or “werewolf family.” This insanely popular trope has taken many werewolf stories by storm, although especially the “shifter romance” genre. I confess I have never read a single book in this genre. I wouldn’t be ashamed if I did and would admit it, but instead I am confessing I actually have no experience with it, so anything I say can be taken with the biases of someone who’s never read one but has heard a gracious plenty through osmosis. They won’t be a focus of this discussion, though.

The focus of today’s thoughts are the concept of the werewolf pack and/or family. It seems like a fun idea in theory, although I still prefer focus on an individual character and back in my childhood they were called “werewolf clans” and I think that is VASTLY preferable, because a group of werewolves should be insanely frightening. Trouble is, it’s almost never done well. I have seen far too many instances of a werewolf requiring a “pack” to even survive (because werewolves suck, apparently?), even to the point of the lore stating a werewolf will outright die if they don’t have some werewolf buddies hanging around because that’s just how their biology works (“biology” and “werewolf” in the same sentence loses me pretty fast anyway though)…

The concept of werewolves having packs and families that they do or must live in is an extremely modern one, for the record. Back in folklore, werewolves weren’t so directly equated with wolves on a biological and behavioral level that they are driven to seek out or live in or create a pack.I think it could be interesting – and in fact I do plan to tackle the concept myself, in a horror way – it just… usually isn’t. Nine times out of ten, for instance, a “werewolf family” is just a bunch of dog jokes bouncing around on trampolines, chasing frisbees, calling each other “pup” and other such terminology, biting at water sprinklers, and barking at the mailman.

There is, as always, a Werewolf Fact for this: https://maverickwerewolf.com/werewolf-facts/packs-communities-and-families/

Image – Sketch artwork for Wulfgard of a group of werewolves, by Saber-Scorpion (our setting in which we create a lot of fiction)

Day 21- Remember how werewolves didn’t used to be considered “diseased” or insane? All that came about in the Early Modern Period, and actually, it’s where we also started using “lycanthropy.”

The word “lycanthrope” in itself is derived from Greek “lykos,” meaning wolf, and “anthropos,” meaning man – which I mentioned before as well. It’s why “lycan” doesn’t make any actual sense and is just word butchery, etc. But referring to the curse of the werewolf (or disease of the werewolf, in most Early Modern cases) as “lycanthropy” became almost the standard, and it was recognized as an illness of the mind rather than a physical affliction that caused transformation. This is one of the many cases of scientific thought attempting to rationalize older stories and beliefs – which, by the way, also led to a great deal of organized and purposeful wolf slaughter (as in, real wolves, the animals) in this time period, far moreso than existed in the past.

When popular culture took the word “lycanthropy” and ran with it, medical institutions started using a different word to refer to those with “wolf madness,” and that’s how we have “clinical lycanthropy” today.

There is, as always, a Werewolf Fact for this: https://maverickwerewolf.com/werewolf-fact-70-werewolves-in-medical-history-clinical-lycanthropy/

Day 22- I’ve mentioned the tale of the Werewolves of Ossory a few times now, so it’s about time I discuss it. I enjoy this one a lot.

This tale comes from Topographia Hibernica, written by Giraldus Cambrensis (c. 1146-1223), also called Gerald of Wales, a Welsh cleric and chaplain. In the story, a priest is traveling when an enormous wolf stops him along the way. The wolf, speaking, humbly and kindly beseeches the priest to help his companion, displaying all good Christian manners. Though reluctant and frightened, the priest follows the wolf back to his companion, a wolf who is sick. The wolf – “using his claw as a hand” – pulls back the wolf skin of his companion to reveal she is an old lady. The priest assists the old woman werewolf, who then returns to her wolf form.

The werewolves explain they are from the land of Ossory, whose people become werewolves as a form of trial; a man and woman take the form of a wolf once every seven years. Mention is made that they were descendants of an Irish warrior, Laignech Fáelad, ancestor of the kings of Ossory. He was the first of his kind to assume the shape of a wolf and go “wolfing,” and his people followed after him.

The first werewolf says he will watch over the priest and his companions for the night and protect them from danger. In the morning, the werewolves bid them on their way, and the priest leaves. He later relays this tale with a moral: do not judge others by their appearance/form, if they be good and kind.

As always, there is a Werewolf Fact for this, in which you can read passages from the story in detail: https://maverickwerewolf.com/werewolf-facts/werewolves-of-ossory/

Day 23- One of the most fun things to a werewolf story is that the werewolf must hide the curse, even from the closest of family and friends. Once everyone else finds out the truth, if they do, it just isn’t as interesting anymore.

This goes back to folklore, too, of course – being a werewolf wasn’t exactly desirable, so even in the stories where the werewolf reveals it to someone else, the other people generally react with horror and fear. Niceros’s Tale, Bisclavret, and many others are examples of this. Sure, there are other examples (like how the king wasn’t bothered in Bisclavret because he saw the goodness in the knight’s heart and behavior), but generally, it wasn’t exactly a good thing. It isn’t super uncommon for the werewolf in the old stories to end up badly, same as in the classic werewolf movies where the werewolf was actually scary*.

Storytelling-wise, it’s just very fun and interesting. It leads to a lot of character questions, moral questions, and generally dramatic situations. If you were turning into a monster, you wouldn’t want anyone to know, either – if you even knew, yourself. More on that part later, though. I just really love stories where the werewolf has to hide the truth from everyone. It’s always so good.

*: The werewolf dying is far from a necessity for a scary werewolf, but the werewolf has traditionally died in the things that are conveying them as truly terrifying, even in some things where the werewolf wasn’t really all that bad or was even a force for good. I’m talking about all those mountains of films that were ultimately offshoots of The Wolf Man (or, it could be argued, offshoots of The Wolf Man because The Wolf Man was an offshoot of Werewolf of London [1935])… anyway. The werewolf dying has become so predictable I just assume it will happen in most of the type of werewolf media I even theoretically enjoy. Not saying I like it, though.

image: concept art for the werewolf from Morrowind: Bloodmoon, just because I love it

Day 24- So I just talked about how much I enjoy the werewolf concealing the curse, something that may or may not always go with that is having no memory of what the monster form did– or, sometimes, not even remembering turning into a werewolf at all. It is, again, another fun layer of drama, character exploration, and meaning that comes with the wonderfully robust tale of the werewolf.

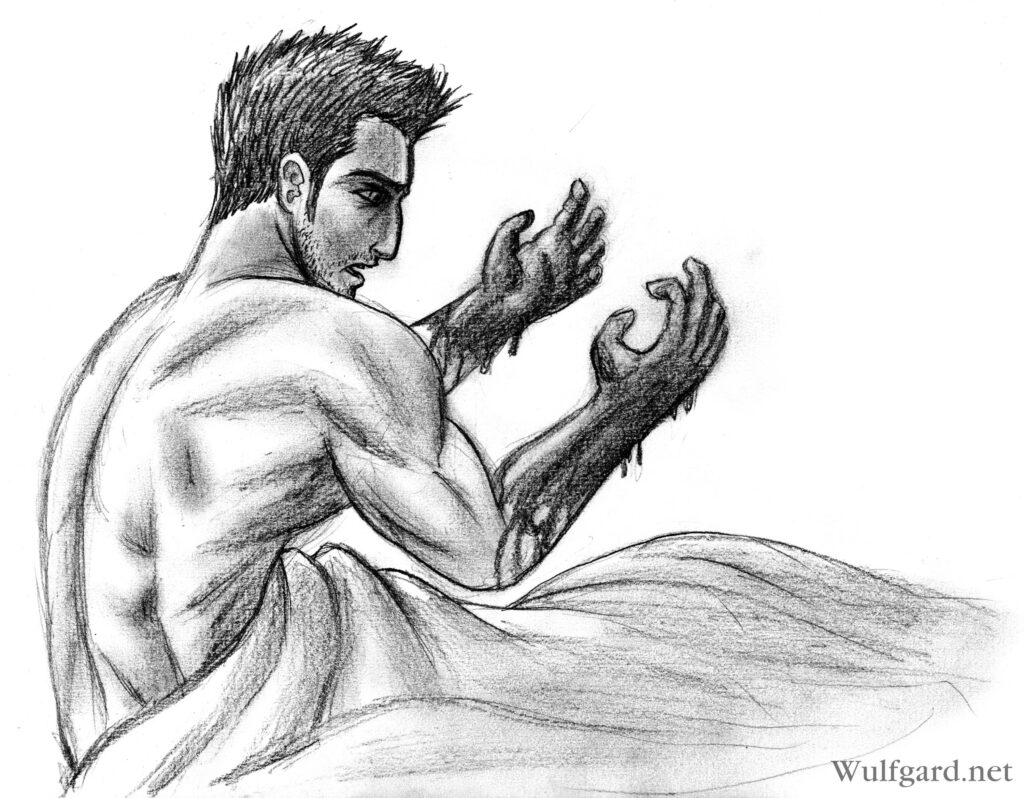

I really cannot emphasize enough how much I love this kind of stuff. Everything about it. But on the subject at hand, the scene of a man (or woman, as the case may be, since we do have those too) awakens in the morning and finds just a few things off – or has literal blood on his hands. Has no memory of what happened. Does he know? Does he figure it out? Or is he left in total confusion? How do things play out from there? What -did- he do last night, and how bad was it? Will anyone else find out? There are so many endless possibilities. It’s something else that I, obviously, love exploring in my own fiction*.

I always address whether or not such a concept existed in folklore, and in this case, the answer is pretty much no. This is yet another thing we can thank The Wolf Man (1941) and writer Curt Siodmak for. So, thank you yet again, Curt Siodmak, for adding another layer onto such a fantastically tragic story.

*: shameless plug for my book coming later this year, Wulfgard: Knightfall, so please check that out; I am currently dying during the editing process and every copy contains a small shard of my soul

img: illustration for upcoming release (Knightfall), by Saber-Scorpion

Day 25- A hill I have chosen to die upon is that portrayals of berserkers as “bear warriors” are wholly inaccurate, preposterous, and baseless. This is considered a sweeping statement in the academic community (because they are the ones who first proposed this utter nonsense, in search of a “new argument” for “the conversation” in the 19th century; before this, everyone accepted that “berserker” means “bare of shirt”), and yet, when I made it, I received support and even a stamp of approval from a lifelong Old Norse and Icelandic scholar and professor. Let me tell you why…

Snorri Sturluson, the historian to whom we owe knowing about almost any of these legends and the preservation or creation of many Sagas and the Eddas, who lived from 1179-1241 AD, has always been the foremost source for all things Norse. It is he to whom we owe a great deal of, and likely even the majority of, our knowledge of Norse mythology. And yet, today, scholars love to disrespect Snorri and claim he was wrong about nearly everything. It’s absolutely absurd.

Snorri said that “berserker” means “bare of shirt,” and I’ve heard many native Icelandic speakers reinforce this theory and other scholars agreeing as well. It refers to throwing off their armor in battle upon entering their rages, or perhaps even fighting shirtless; there are arguments about that too. Many scholars still refute this idea of berserkers being bear warriors (there are numerous examples, such as Anatoly Liberman), and some don’t even bother acknowledging it; you can find some things today that, thankfully, don’t touch this bear concept at all, especially outside of America. Huge props to Robert Eggers for his incredible research for The Northman film and an execution that resulted in the coolest portrayals of a berserker that we have ever gotten, and that feels accurate to the sagas. Modern scholars like to say that Snorri was very wrong and that “berserker” means “bear shirt.” They refute Snorri for saying that his theory has been abandoned because of “lack of supporting evidence,” which is so rich because they have no supporting evidence for their “bear warrior” etymology, either.

Long story short, I will not stand for Snorri disrespect. We love Snorri in this house.

Now, on to berserkers themselves. Why do I insist, then, that they are wolf warriors? We have many examples of what are sometimes called the ulfheðnir, or “wolf-shirts.” Note that you recognize the Old Norse form of wolf in “ulf,” same as you generally would recognize “bjarn” or “bjorn” for bear*. An ancient Roman account describes them thusly: “Their eyes glared as though a flame burned in their sockets, they ground their teeth, and frothed at the mouth; they gnawed at their shield rims, and are said to have sometimes bitten them through, and as they rushed into conflict they … howled as wolves.”

Berserkers were described variably as “strong as bulls,” “howled like wolves,” and other animal comparisons. But, more often than not, we see berserkers associated with wolves across the sagas. They were said to enter mad rages, their berserk state, during which they endured impossible amounts of pain, were unharmed by fire or iron, and performed superhuman feats of strength and bravery. They were sometimes called hamrammr, or shape-strong, and it is implied they are stronger than an ordinary man no matter what shape they currently took. Some were associated with shapechanging, such as Kveldulf the evening-wolf, a highly intelligent man sought for his wisdom – but, around dusk each day, “he became so savage that few dared exchange a word with him … People said that he was much given to changing form, so he was called the evening-wolf, kveldúlfr.” Kveldulf appears in multiple sources, such as Egils saga and more. Other ulfhednir appear in the Vatnsdæla Saga and the Holmverja Saga, among others, with several being cited as capable of changing forms and “wolf-shaped.”

Also, not only is there a suspicious lack of named bears in Norse myth as a whole (though we have many named wolves, a named boar, named goats, ravens, and even named roosters, squirrels, and more) to claim they are so important to their culture historically, but again, we are notably lacking in direct evidence of this “bear warrior” concept. Some love to cite Bodvar Bjarki from Hrólfs saga kraka – a warrior who could assume the shape of a bear – but he specifically was NOT a berserker, and in fact he frequently came in contention with berserkers and talked down about them.

As you can see, I could go on about this for quite some time, and I plan to at some point. There’s a lot more to say and discuss, but I’ll leave it off here for now.

More on this in a huge article sometime next year, probably. Way too much work left in this year. I do have this one, however, that I wrote many years ago now and have expanded upon some since, though it requires far more expansion and specificity (some of which I did here instead): https://maverickwerewolf.com/werewolf-facts/berserkers/

And this is also discussed in my book, The Werewolf: Past and Future, which I will always shamelessly plug as a great way to get started with the werewolf legends throughout the march of history: https://www.amazon.com/dp/1949227022

And also my own edition of Sabine Baring-Gould’s fantastic work from the 1800s about werewolves, includes footnotes, translations, etc by yours truly; he discusses the sagas quite a bit: https://www.amazon.com/Book-Werewolves-Superstition-Annotated-Translated-ebook/dp/B0CK4YY16Z

*: why aren’t they called “bjarnskins,” then? Why would berserker begin with a Proto-Germanic “bero” for bear when “berr” is Old Norse FOR BARE, like “bare of shirt”?? A form of “berr” meaning “bear” did not exist in Old Norse. Why does anyone even believe this bear warrior berserker crap?

image: helmet plate from the Vendel period (540–790 AD) depicting Odin and a wolf-cowled or wolf-headed berserker

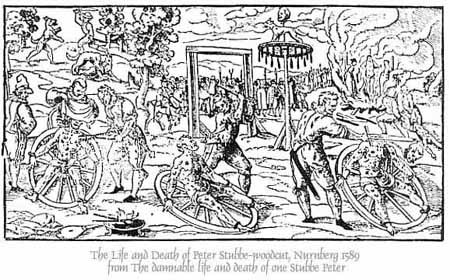

Day 27- Alright, remember how I’d die on that berserker hill? This is my other hill. “The Werewolf of Bedburg,” Peter Stubbe or Peter Stump or Stumpp, is considered one of the most famous werewolf legends. Problem is, it is not a werewolf legend. Let me tell you why.

Firstly, let’s begin with the legend itself. I will be pulling quotes from The Werewolf in Lore and Legend by Montague Summers. It’s a good werewolf book, but Summers sometimes contradicts himself in his ramblings and sources, so you have to study it carefully. Overall, though, it’s a very good work and very good for cross-referencing. His account of Peter Stubbe is one of the best elements of the book.

Peter Stubbe was a man who used satanic magic (“Damnable desire of magick … and sorcery”) to assume the shape of a wolf and commit terrible crimes. The works specifically say that the devil may grant followers “the shape of some beast” (it was not always a wolf; witches took the forms of many, many animals) in order to “live without dread or danger of life, and unknown to be the executor of any bloody enterprise.” Stubbe asks for the shape of “some beast,” not a “wolf” specifically. However, the devil gives him a girdle that allows him to “transform into the likeness of a greedy devouring wolf, strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkled like unto brands of fire,” among other description. Should he remove the girdle, he would become human once more.

This separates him from other werewolf accounts and tales of his era in that he asks for no specific animal and the court ruled him a “sorcerer,” not a “werewolf,” unlike – for example – Jean Grenier, whose tragic tale took place in 1603. Stubbe would “ravish” children and women and devour them, as well, something never before associated with werewolves. And not since, either, until these wonderful modern scholars latched onto Stubbe and decided his trial was a werewolf trial, even though it wasn’t. So we have even more quotes about how he committed “devilish sorcerie [sorcery],” no reference to lycanthropy or werewolfery or anything else as such, while he went about performing atrocities like killing, devouring, and violating women and children, including Stubbe’s own sister. And no matter how many times he is referred to as a “wolf,” he is never called a “werewolf” even once.

Tales of “witch-creatures” exist that are apart from werewolf legends and other sorts of monster legends due to the fact that witches and/or sorcerers were very unique and important entities during their time. Stubbe’s account concludes,

“Thus Gentle Reader haue I set down the true discourse of this wicked man Stub Peeter, which I desire to be a warning to all Sorcerers and Witches, which vnlawfully followe their owne diuelish imagination to the vtter ruine and destruction of their soules eternally, from which wicked and damnable practice, I beseech God keepe all good men, and from the crueltye of their wicked hartes. Amen.”

Note: sorcerers and witches again. No mention of werewolves.

Stubbe was executed in Bedburg, near Cologne, on the 31 of March 1590. He has a pamphlet from the time period, as his case and execution created quite the stir…”

A true Discourse.

Declaring the damnable life

and death of one Stubbe Peeter, a most

wicked Sorcerer, who in the likenes of a

Woolfe, committed many murders, continuing this

diuelish [devilish] practise 25. yeeres [years], killing and de-

uouring [devouring] Men, Woomen, and

Children.

Who for the same fact was ta-

ken and executed on the 31. of October

last past in the Towne of Bedbur

neer the Cittie of Collin

in Germany.”

Note that he is referred to as a “Sorcerer,” and again, another discourse about the case from the period refers to him as “Stubbe, Peeter, being a most / wicked Sorcerer.” Works from Stubbe’s time period and covering Stubbe’s trial never once refer to him as a “werewolf” or reference “werewolfery” (a term seeing relatively frequent use in this era). He is repeatedly referred to as a sorcerer and using sorcery, and he is even once called a “hellhound,” but he is never directly called a “werewolf.”

Here’s where the issues start. Peter Stubbe lived during a time period when people were, in fact, still using the term “werewolf” (and/or “loup garou” and other terms) in a fashion almost as categorical as what we use today. This is in opposition to older time periods that didn’t collect and classify legends and monsters and declare they’re all madmen and rationalize them in the face of scientific thought. This was entering the Early Modern Period, when werewolves became seen as madmen and belief in them justified via diseases and insanity. Many other werewolf trials occurred before, after, and during the time of Peter Stubbe, and they were specifically called “werewolves” in their trials. For example, a decree issued by the parliament of Franche-Comte in 1573 – years before Stubbe’s trial – specifically orders that people “chase and pursue the said were-wolf in every place where they may find or seize him” (after properly arming themselves with “pikes, halberds, arquebuses, and sticks” of course).

Peter Stubbe, however, was not. He was only ever referred to as a “sorcerer.” If you’ve read the Malleus Maleficarum and other, similar works of these eras, you would know how important classification of such things was during the time period, and why it is important to recognize the differences among witches, “witch-animals,” werewolves, and other beings ranged from cursed to satanic to insane to everything else. His case also lacks integral elements to werewolf trials of the time period, such as the lack of self-control and declared insanity (remember, werewolves were associated with madmen at this time).

Scholars only started referring to Peter Stubbe as this “Werewolf of Bedburg” in later time periods. Calling him a werewolf at all is very much a machination of modern scholarship and academia and a distortion of werewolf legends that has in turn led to some misconceptions about werewolf legends as a whole.

And if you think I’m just being pedantic, I’m a scholar and historian. It’s what I do. Preserving things as they were actually believed in during their own time periods is important. Calling this a werewolf legend and/or account is simply inaccurate, and it never should have happened. Peter Stubbe’s trial was not a werewolf trial. It was a sorcerer trial.

There is a very large Werewolf Fact for this. I go into laborious detail here, with many quotes, citations, and further discussion of this entire concept and its lasting importance: https://maverickwerewolf.com/werewolf-of-bedburg-peter-stubbe/

This is, again, also something I discuss in my work, The Werewolf: Past and Future: https://www.amazon.com/dp/1949227022

img: woodcut depicting “The Life and Death of Peter Stubbe,” 1589

Day 28- I have all too often seen assertions that “werewolves don’t have tails,” as if there are facts to be had about a mythical creature at all and as if this is a certainty. If we could theoretically have any facts about werewolves (as is my nonfiction branding), we would turn to folklore – which explicitly states that yes, werewolves have tails. What’s more, having a tail is what separates a werewolf from other mythical beasts.

This begins not only in the fact that werewolves in folklore are often described as being wolves, often very big ones, without mention of lacking a tail, but more specifically in that the Early Modern Period, a differentiating factor between werewolves and witch-creatures was a tail.

In 1590, Henry Boguet in his treatise “Of the Metamorphosis of Men into Beasts” says specifically that the difference between a werewolf and a witch that has turned into a wolf is that witch-animals have “no tails.” This is in fact true of every witch animal, apparently. And yes, in this time period, again, they did in fact differentiate between a werewolf and a witch who turned into a wolf. This specificity persists in the Malleus Maleficarum, specifically question X of part I, “Whether Witches can by some Glamour Change Men into Beasts,” which states, “the devil can deceive the human fancy so that a man really seems to be an animal.” This is a deception, not a transformation, as we generally get with a werewolf. Furthermore, “no creature can be made by the power of the devil, this is manifestly true if Made is understood to mean Created. But if the word Made is taken to refer to natural production, it is certain that devils can make some imperfect creatures.”

Bear in mind that there were some works in this time period that considered werewolves to be related to witchcraft but not entirely equal to it. Generally, a werewolf becomes a werewolf and is out of his or her own control, unlike a witch, who undertakes such practices willingly. The idea of witches being “imperfect” animals persists in many works of this time.

Not saying this to rip on the tailless werewolves of popular culture, though. Just providing context. I actually fully understand not wanting your werewolf to have a tail. While I don’t think having a tail inherently makes a werewolf “cute,” and I personally will always battle tooth and nail against that, I also understand that having a tail could insinuate “cuteness” to certain modern audiences in particular. Perceptions change over time, and this is definitely one that has. I also realize that tails are frequently left off of film werewolves because they’re very hard to create in a convincing way, and then regardless of anything someone might be capable of creating today, the design concept kind of stuck in film.

I also often hear excuses that “people will be attracted to the monster” (to put it in more socially acceptable terms, but I’m sure you know what I mean) and that’s supposedly a justification for making werewolves look like naked mole rats with scabies and mule faces and bulging eyes and arms longer than their legs, but honestly, someone’s going to want to screw even that thing. And tail or no tail, regardless of design, this definitely still applies. I don’t think such a discussion has ever been held in the boardroom of a major film project (no one cares), but I’ve seen it discussed on the internet, and I don’t think those internet people should let other internet people dictate monster design or perception to them.

I also still think a tail as a sign of inhumanity can still hold frightening power, as long as it is presented properly. A tail is something humans do not have – only beasts have tails. To grow a tail is a sign that one has truly become something other than human – a werewolf turning into a monster.

I will continue the fight. My terrifying werewolves have tails… mostly just because I think it looks better as a design choice instead of a tailless human rear like a donkey without a pinned tail, as pictured here on The Howling werewolf.

Day 29- It’s almost Halloween! Honestly, my very favorite kind of werewolf could essentially be summarized as “the Halloween werewolf,” which is of course very inspired by The Wolf Man (1941). I love the spookiness, the classic horror, even the way they’re generally lit. I love the dead black trees, haunting graveyards, the full moon, the tattered clothing, the bite that can make you share in its curse… and the promise that behind that terrible wolf-beast is an innocent man.

Even just seeing werewolves like the classic Halloween kind inspire me to an incredible degree. They fill me with joy and set my imagination aflame. They always have. I love their motifs and how they’re portrayed, everything from scary old horror movie werewolves to spooky Halloween setups with fog machines to silly cartoon Halloween werewolves. I’ve adored them since day one, and really, the werewolves that come out at Halloween are the ones that made me fall in love with the concept and legend of the werewolf.

I’ve always used these classic motifs to inspire my own fiction (and Halloween monsters and atmosphere is like my entire thing) because they do make me so happy and give me so many thoughts and ideas and put so many stories into my head. Did you know, too, that the idea of a werewolf stalking a graveyard (as Halloween werewolves often do) also comes from folklore? Werewolves were often associated with sites of the dead – like many other wolf entities – and could be found in graveyards digging up graves and devouring the corpses, in many stories.

So, although I have so many thoughts and rants and raves and research and countless stories to write and folklore to preserve, I’ll always be inspired the most by the simplest werewolf concept: the ones that come out at Halloween.

Day 30- This one might seem like it’s coming out of the left field, but I overthink every single aspect of werewolves and also their designs, so naturally I have thought long and hard about what ears look coolest on a werewolf. I’ve come to the conclusion that a werewolf needs big, scary ears. They’re just badass and really emphasize the wolf aspect.

No, I’m not talking about cute ones or the silly ones or the big lynx-bunny ones (sorry, The Howling, but you went seriously overboard). I’m talking about horror werewolf style emphatic beast ears. If your werewolf has short, squat, or rounded ears, it ends up looking more like a bear. I’m talking much more like Anubis. Man, those werewolves look so awesome. But, obviously, the usual wolf ears are great, too. I also have gained a considerable fondness for the Underworld like William Corvinus style side-of-the-head ears, as long as they’re sufficiently long and pointed.

But these werewolves that have really small and de-emphasized, rounded ears? Yeah, they mostly just look like bears or something. Ears are so important. Even on wolf-men, I think bigger, pointed ears help emphasize the inhumanity and the wolfishness. It makes them scarier.

img: some werewolf from a thing called Horror Legends? I actually have no idea what it is, but I’ve seen this image going around and I just really love this design

Day 31- Happy Halloween! For the final day, I just want to expand upon how, as preposterous as it may seem, I really cannot put into words how much the concept of this curse of the werewolf captivates me. There are endless elements to explore and stories to tell with such a thing (and I am going to tell as many as I can, myself, in my own fiction). The distant howl of a beast, wolfish yet wrong, drifting over the graveyards and haunted forests under the light of the full moon as the air hangs thick with fog– knowing it is the voice of a cursed monster but also of an innocent soul, haunted, powerless, enduring the untold agony of the transformation and now indescribably dangerous… cursed, lost in rage with which no man could contend, and always starving for flesh.

It is one of the deepest tales of tragedy. The werewolf is a being of duality, of halves, never to be truly whole. Neither a man nor a beast, they must wander, alone, lost, at odds with themselves, in sorrow, fury, and eternal hunger. How does one reconcile committing atrocities in the skin of a beast? How can any good person continue as such a monster?

It gives me chills just thinking about it. I’ve never seen a concept cooler, and I know I never will. You cannot best the oldest of legends and such a core terror that haunts all humanity: the idea that even the most civilized a man could become the most terrible of beasts. This is why werewolves have haunted the human psyche since the dawn of time – and they always will.

Obviously, there are many takes on werewolves, especially these days, and not all folklore told such tales, but I’m speaking in terms of why werewolves captivate me personally. To me, it all comes back to The Wolf Man (1941), as inspired by legends and turned into a tale of tragedy that touches the hearts of all who hear it. You cannot help but relate to such a character, feel sorry for him, but you always must wonder… what would you do, in such a situation? What would you do, as a werewolf – or as a werewolf’s loved one? What would you do, if someone you cared about turned into a monster?

That is untold narrative power.

As always, I have endless werewolf thoughts all the time, not to mention publishing werewolf articles, folklore research, and much more. I am also finally getting into publishing my werewolf fiction, which has always been my truest life goal.

November this year (or December if things go sour for me, but hopefully November), I will have a new release called Wulfgard: The Prophecy of the Six, Book I – Knightfall. It’s the biggest deal to me. I’ve worked on this story my whole life and been editing this huge revision of it for almost ten years. It means so much to me. And I’m so proud of it. I can’t wait to publish it and share it with the world.

I really hope you’ll check it out. So be sure to check back with me for its release and pick up a copy (or maybe even take part in some fun giveaways and other things I have planned). It’s kind of like Lord of the Rings meets The Wolf Man. If you love traditional fantasy, adventure, horror, werewolves, knights, mystery, and even pitched battles, this book has it all.

For now, though, I have to get back to work on said book. I hope my werewolf post series here has been fun, thought-provoking, and even educational. I do this kind of thing all the time, but I’ve never done a once a day series. It’s been a blast.

So, once again – happy Halloween!

img: art of werewolf Tom Drake from Wulfgard, by Saber-Scorpion