Folklore Fact – Wargs (or vargs or worgs)

Wargs (aka worgs, if you play D&D) handily won the poll for August’s folklore fact. What are these giant wolves like, anyway, and are they really all evil in legend?

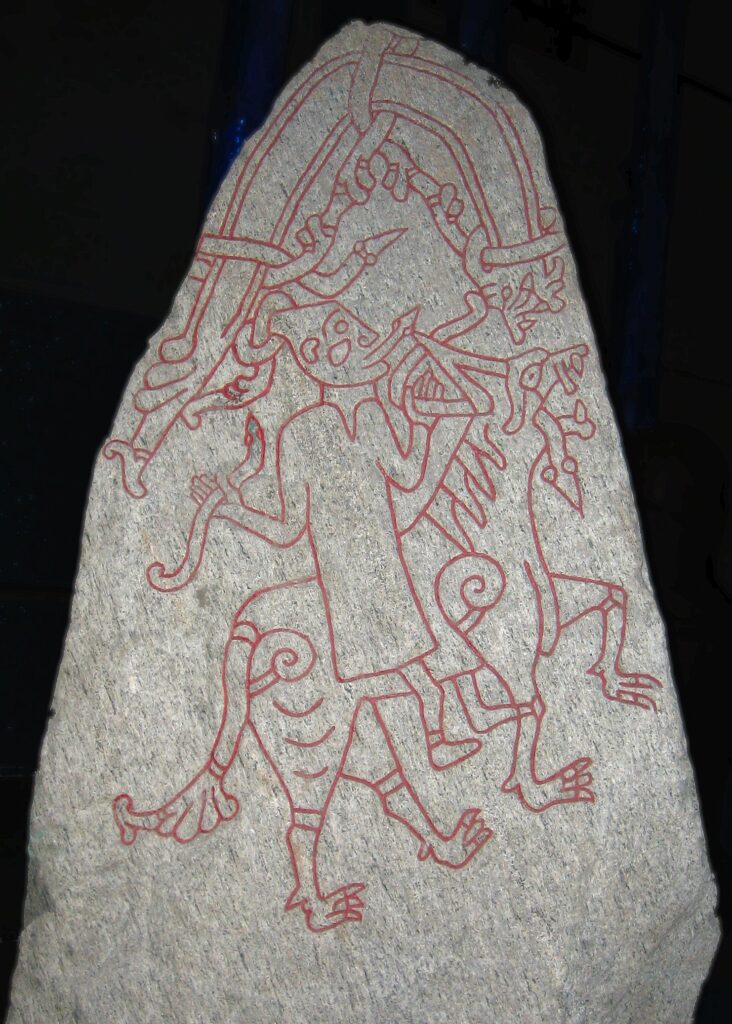

The jötunn Hyrrokin riding a wolf, on an image stone from the Hunnestad Monument, constructed in 985–1035 AD

As usual, let’s start with etymology. The word “warg” comes from Old Norse “vargr” (plural “vargar”), meaning – essentially – “destroyer.” Originally, the term is thought to have meant “wolf,” but over time, it shifted to refer to criminals (with an inherent negative meaning) instead. Thanks particularly to Tolkien, it is now widely used in scholarship to refer to the various giant wolves of Norse mythology, such as perhaps the mightiest and most terrifying monster in Norse myth, Fenrir (destined to swallow Odin during Ragnarok), along with Skoll (destined to swallow the sun) and Hati (destined to swallow the moon).

Note that this was not the common Old Norse word for wolf. “Varg” came to have a specifically negative connotation, whereas “ulf” (meaning simply “wolf”) did not.

There were also plenty of other wargs/giant wolves in Norse myth, often being used as mounts to various gods and giants and other extremely powerful individuals; they were particularly favored of the jötnar, who, despite the simplification in a lot of modern media, were not always universally malevolent and hostile toward the gods. The runestone seen above depicts the giantess Hyrrokin who arrived to assist the gods with shoving off Baldr’s funerary ship during Baldr’s funeral, as no one else could move the vessel. She arrived riding on the back of a huge wolf so mighty that, after the giantess dismounted, even Odin’s berserkers could not restrain it until it was knocked unconscious.

Does this also make Odin’s wolves, Geri and Freki, “wargs” in the modern scholarly concept? That was never really specified. But they are giant, godly wolves, perhaps meant to be the fathers of all wolves everywhere, so… Maybe? In some tales, during Odin’s wanderings, Geri and Freki spread their wolf offspring across the world. Thus, it is possible they are simply giant godly wolves rather than specifically “wargs,” but it’s also possible that mythology wasn’t ever planning to be that nitpicky and specific. Odin was, of course, also the creator of the berserkers, which gives him yet another wolf connection.

Going back to etymology for a moment, “ulf” was frequently incorporated into personal names. Wolves were not seen as wholly undesirable in Norse culture; to claim wolves were always seen as “evil” or somehow “negative” is to simplify the concept beyond belief. Wolves were admired for their fabled ferocity, endurance, will to live, voracity, and prowess in battle. Thus, wolves became a symbol of strength and a desirable image for great warriors. Though often feared, this fear is precisely what led many warriors to desire to be like a wolf, for they too desired ferocity feared by those around them. Wolves were a force of nature, an uncontrollable power to be respected (such as the power of the berserkers, again, who themselves were associated with wolves and, despite their connections with the god Odin, were also at once frequently seen as undesirable but worthy of respect), not simply a force of black and white “pure evil.” How terrifying they were led to wolves becoming arguably the most powerful and feared monsters in Norse myth, but likewise, it was an image their warriors often wanted to take up and present.

While the majority of named giant wolves from Norse myth are certainly evil, such as Fenrir, what truly popularized the modern concept of the evil wargs in popular culture was – of course – the father of all fantasy and unmatched scholar JRR Tolkien. Likewise, Tolkien popularized the idea of goblins and/or orcs riding giant wolves into battle, no doubt inspired by the jötnar of Norse myth. Obviously, Norse and other myths greatly inspired many elements of The Lord of the Rings. Wargs are no different, but he did of course put his own interpretation upon them – an interpretation that has, like so many of his creations, become staples of many fantasy settings and even the popular mindset.

Whereas wargs in myth are at least semi-divine mounts of gods and giants, the wargs by the Third Age of The Lord of the Rings are mounts for goblins and their ilk. However, the wargs are intelligent and even have a sort of language, one some beings (such as Gandalf, notably inspired to no small degree by elements of Odin, himself) can understand, even if it is an evil tongue and they use it to speak only of evil things, as seen in The Hobbit. In the books, the wargs are often associated with Tolkien’s very unfortunate portrayal of werewolves. I won’t get into all the details of that. I adore Tolkien and all his works beyond my love for virtually anything else, but I cannot say I love his portrayal of “werewolves,” though I do understand them.

So where then do we get this spelling of “worg?” That’s entirely Dungeons and Dragons. Oldschool D&D wholesale ripped off Tolkien – which is one reason why oldschool D&D is so great – and had to change some of the terms they used. Balrog became balor, hobbit became halfling, mithril became mithral, etc. The same applies to “warg,” Tolkien’s term, which became “worg” in Dungeons & Dragons.

So where does this leave A Song of Ice and Fire aka Game of Thrones, with the “wargs” that are “skinwalkers” who can “warg” (verb) into animals, etc, and see through their eyes? There were plenty of legends out there – from Norse myth and otherwise – wherein people could project their consciousness into the bodies of animals when they slept or otherwise entered a kind of trance (some legends that could be considered werewolves also worked this way), but the term “warg” was never used to refer to such acts.

Ultimately, the modern concept of wargs is yet another major fantasy element that Tolkien alone conceptualized into what it is now in broader popular culture. Yes, it is certainly based on Norse myth, but Tolkien is the one who gave us our popular concepts of them today.

That’s it for a general overview! This is a vast topic into which I could delve far deeper, but now you should have some general idea.