Vrykolakas

Time for a loaded subject – vrykolakas.

So what the heck is are vrykolakas, anyway?

There’s a lot of dispute over exactly where the term comes from and what on earth it’s referring to. Ask any scholar in the field and they’ll give you at least three different answers. It’s a tangled web.

So let’s go over a few:

If you ask one scholar, Sabine Baring-Gould, the vrykolakas were essentially werewolves and vampires. A werewolf in life, a vampire after death.

But they weren’t “werepires” (please do not use that word in my presence) in the sense of “werewolf-vampire hybrids,” i.e. werewolves that drink blood and have bat wings or, if you’re Underworld, blue-skinned people with black eyes who seem to have the qualities of neither creature.

BUT other scholars dispute even this, such as H. F. Tozer, who says that this is a mistake and “in the great majority of cases the werewolf superstition is wholly independent of this belief … [and] one writer, who has carefully collected authorities on the subject, expresses his opinion that the nature of the werewolf is no longer to be recognized in the modern Greek Vrykolaka.” Who is this writer, and what authorities he has collected, we don’t get the benefit of knowing.

Tozer discusses various possible ways this mistake could have been made, such as that in Greek myth, people could turn into vampires after death by eating lamb killed by a wolf. But he, of course, acknowledges that werewolves have been well-established in Greek myth since classical antiquity.

Then we have a fellow named M. Robert, who said that, essentially, there were “voukodlaks” that were vampires, and he cites the word as meaning “werewolf.” But he describes them as vampires that turn into wolf-men during the full moon, and go out to drink blood. Sources? No idea. I take this one with a grain of salt.

And then you also have scholars arguing vehemently (and I of course agree) that all of this confusion doesn’t mean that there is not a very clear distinction between vampires and werewolves – vampires are “dead [bodies] which continue to live in the grave, whence it issues by night for the purpose of sucking the blood of living persons, and thereby indefinitely preserving its vitality and securing the carcass from decomposition” (as Montague Summers says in his book, Werewolf, page 151), going on to describe his personal idea of werewolves.

Then you have another scholar, Lawson, who says that “The Slavs brought with them into Greece two superstitions … The old Hellenic belief in lycanthropy was apparently at the time weak–confined perhaps to a few districts only–for the Greeks borrowed … the word vrykolakas in place of the old [word], by which to refer to the idea of a ‘werewolf.’” (Werewolf, Summers, 151).

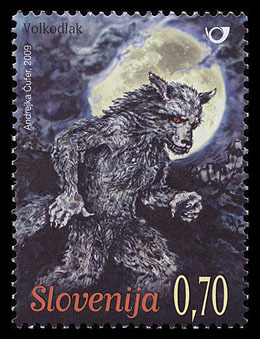

Then, Serbians and Croatians have a creature, ‘vukodlak’ or ‘volkodlak,’ mentioned in a previous post or two, and that word essentially means “wolf’s hair.” Does this refer to werewolves or to vampires? Who knows? The postage stamp pictured at the top of the post argues that a volkodlak is a werewolf, but scholars are still all in a tizzy about it.

So what the heck is a vrykolaka? Who knows? Maybe it’s a werewolf. Maybe it’s a vampire. Maybe it’s a werewolf that turns into a vampire after death.

We really have absolutely no way of knowing, with all this confusion! Welcome to the world of folklore studies. But from the look of things, it seems that, in Greek, “vrykolakas” may no longer refer to werewolves (although this is disputed!) and instead refers to a vampire of some kind and possibly one related to wolves somehow, either in how they became a vampire or that they are a vampiric wolf.

But, in Eastern Europe, similar term “volkodlak” refers to a traditional werewolf, as seen on the postage stamp.

But what do these words themselves actually mean, etymologically? They both technically mean werewolf.